In 612 began the rule of Muwaan Mat – the same name as an ancestral deity of the site. Muwaan Mat’s identity remains enigmatic, but may have been the mother of, and regent for, Palenque’s most famous king, K’inich Janaab’ Pakal l (“Pacal” or “Great Sun Shield”), who assumed power in 615 at age 12 and ruled until 683. Pakal is one of the best known Mesoamerican kings, famed for his mortuary monument. Yet his reign was not easy. His kingship to Palenque’s established dynasty was, at best, tenuous, and his reign was mired in foreign conflict. Yet Palenque’s “greatest artwork and longest texts emerged as reactions to the defeat and breakdown of its royal line, as new dynasts strove to legitimise and consolidate their power” (Martin and Grube 2000: 155).

Funerary Dress of K’inich Janaab Pakal I.

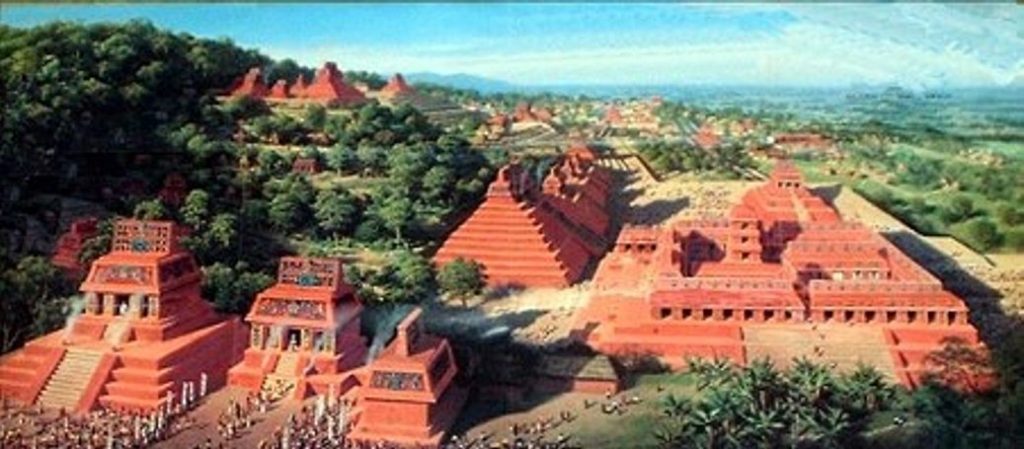

For example, the palace was built on an Early Classic foundation, a platform measuring roughly 58 by 79 meters (190 by 259 feet). Pakal’s rooms and courtyards created an administrative residence that dominated the central part of the site. The palace had facilities for ceremonies and receptions, plus amenities like sweat baths and latrines. The design also included architectural innovations to increase the span encountered by the corbeled vault, and also to reduce the weight displaced to the walls, by the use of mansard-style roofs.

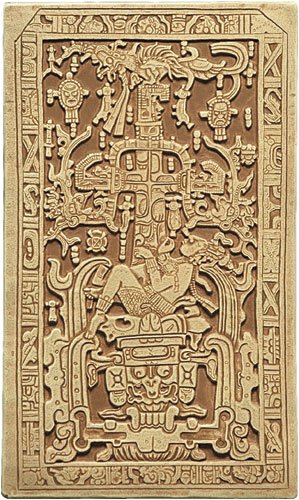

Pakal is even more strongly associated with his own funerary monument, the temple of the inscriptions. The design of the sarcophagus and its cover made it possible to ready the tomb, and then, after Pakal’s death, inter the body and slide the cover over it. The, the coffin was connected to the temple atop the pyramid by a “psychoduct” or “spirit tube” – a pipe built into the stairway, by which Pakal’s descendants could contact his spirit. The tomb was plastered shut, and in the anteroom five captives were sacrificed to be Pakal’s companions on his trip to the otherworld. These rites of passage completed, the mourners would ascend the stairs and emerge in the temple of the inscriptions, performing more rituals in sight of the assembled Palenqueans in the plaza below. Such rites, private and public, would assure a safe transition through the dangerous liminal state of passage from the world of the living to the realm of the dead, for Pakal’s spirit and Palenque’s political stability . However, Pakal’s 7th century reign was Palenque’s time of greatness. The dynasty struggled along until around 800, but soon thereafter, was abandoned (Mathews and Schele).

The Cover Of Pakal’s Tomb

The above is an extraction from the book, Ancient Mexico And Central America: archaeology and culture history written by Susan Toby Evans.